For our 605 studio, we were tasked with a very specific program on an industrial site in Deep Ellum, in Dallas, Texas. For the program, we were to design a community center that would also function as an archive and gallery space for the works of Donald Judd. For those unfamiliar, Donald Judd was a renowned artist who designed pristine, industrial, and machined sculptures in the mid to late 20th century. Famously, Judd designed his works and had them produced by craftsmen and machinist, with extreme precision. After a successful art career, Judd moved to Marfa, Texas, and is responsible for the town’s revival and ascent as a sort of artist pilgrimage site. Judd would open an architecture studio in Marfa, but would tragically pass away before the firm could do much work.

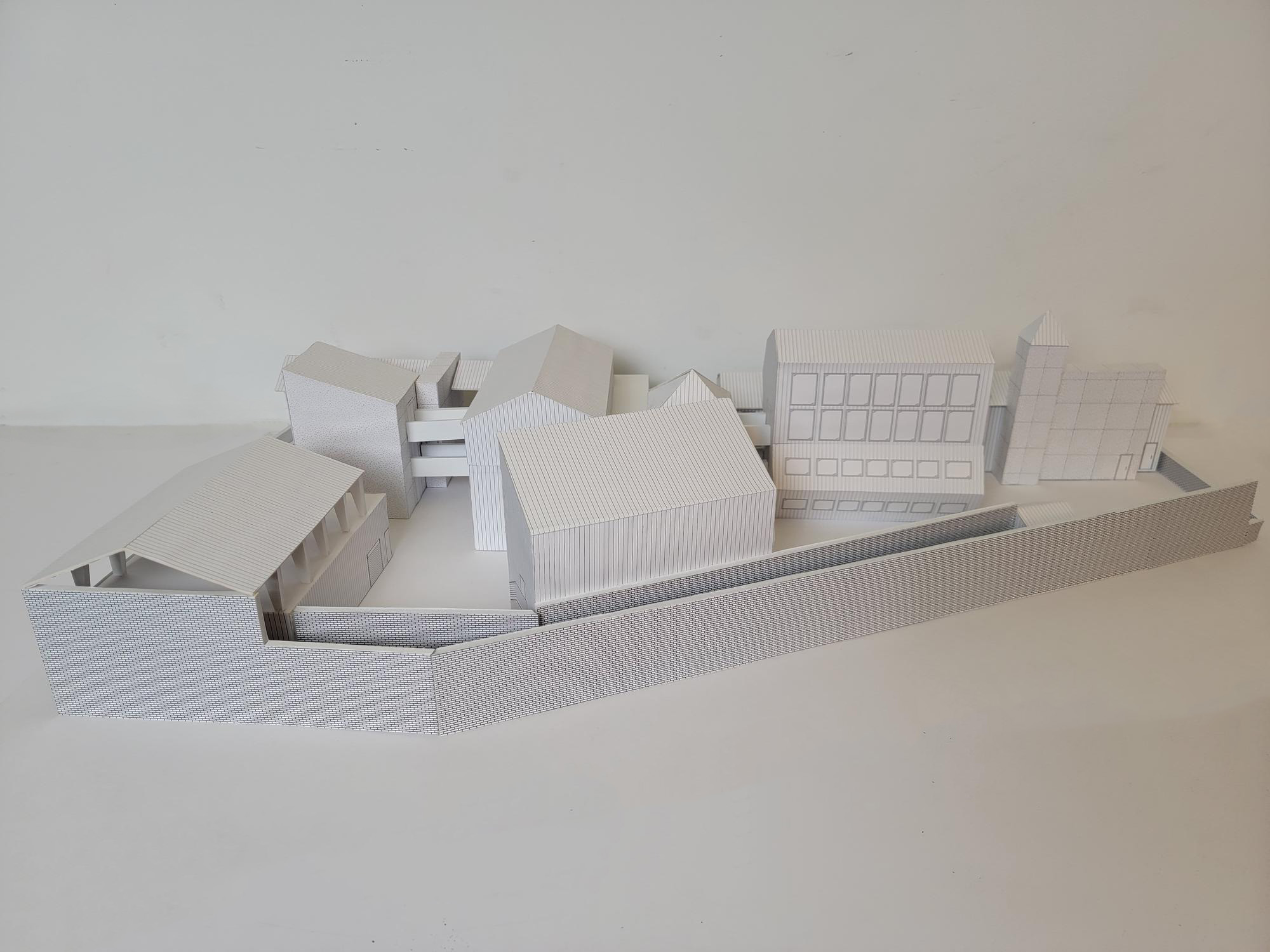

For our project, we were given a site in an industrial neighborhood in Deep Ellum. The site sits between two highways and is adjacent to a train-yard. Around the site are mostly prefab metal buildings and warehouses, with only a handful of run down houses near the site. The site also happens to be in a very high crime area (at least at the time of the design) and next to some small homeless encampments. Needless to say, designing a community center that would also house priceless pieces of art in a dangerous and hard to access site posed many design challenges. To address the difficult site and program combination, a few primary design choices drove the bulk of the project and its design.

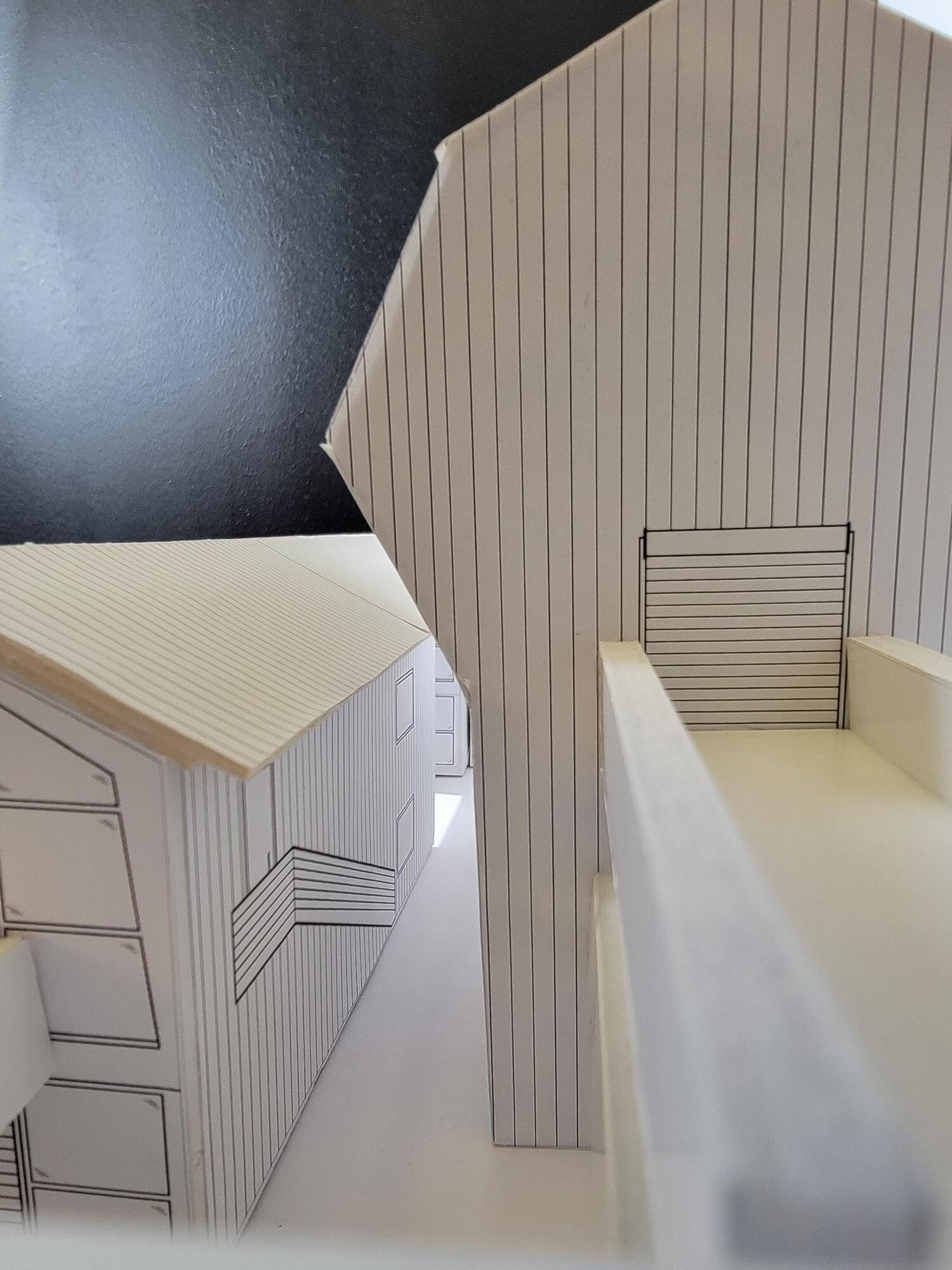

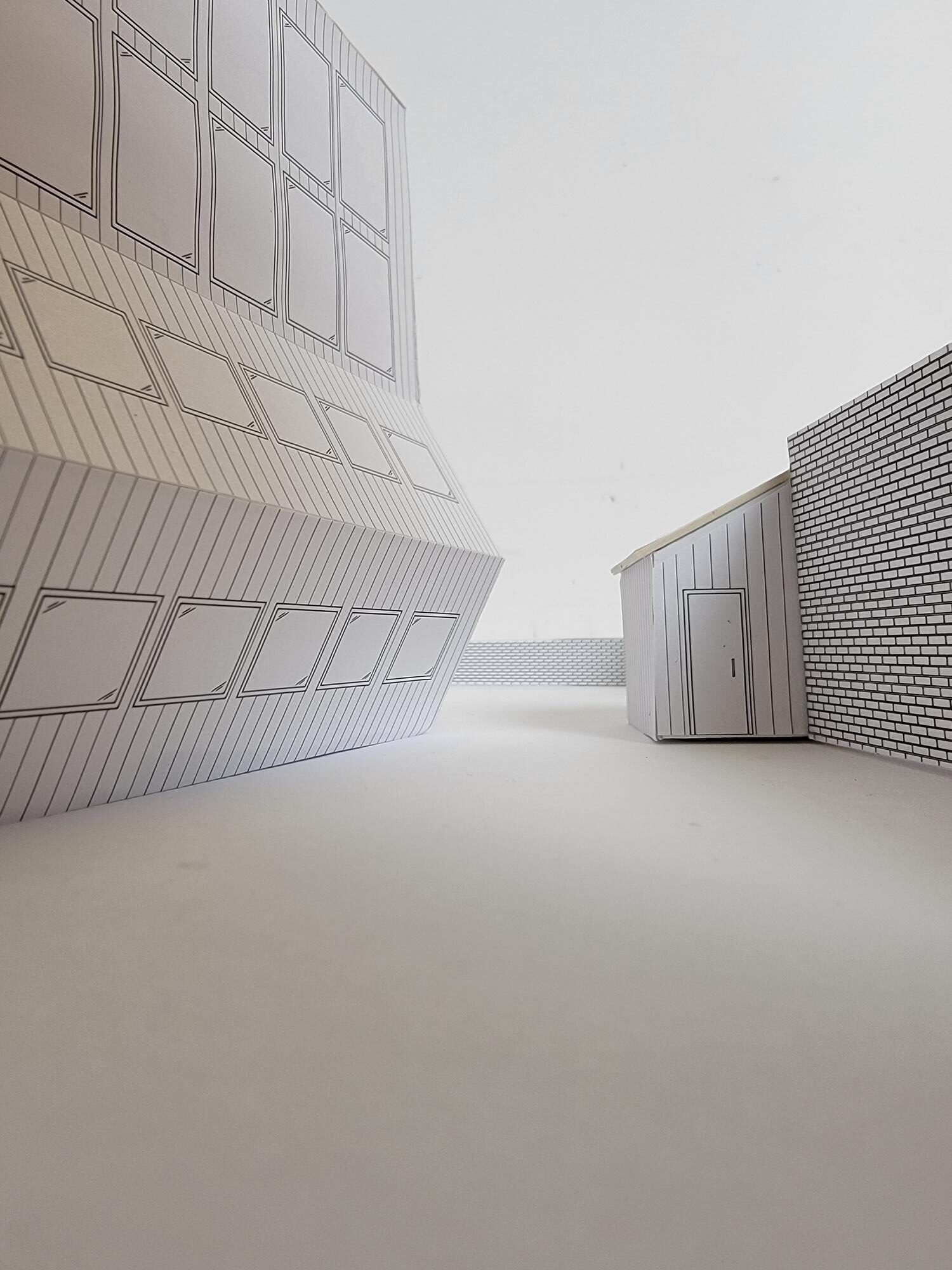

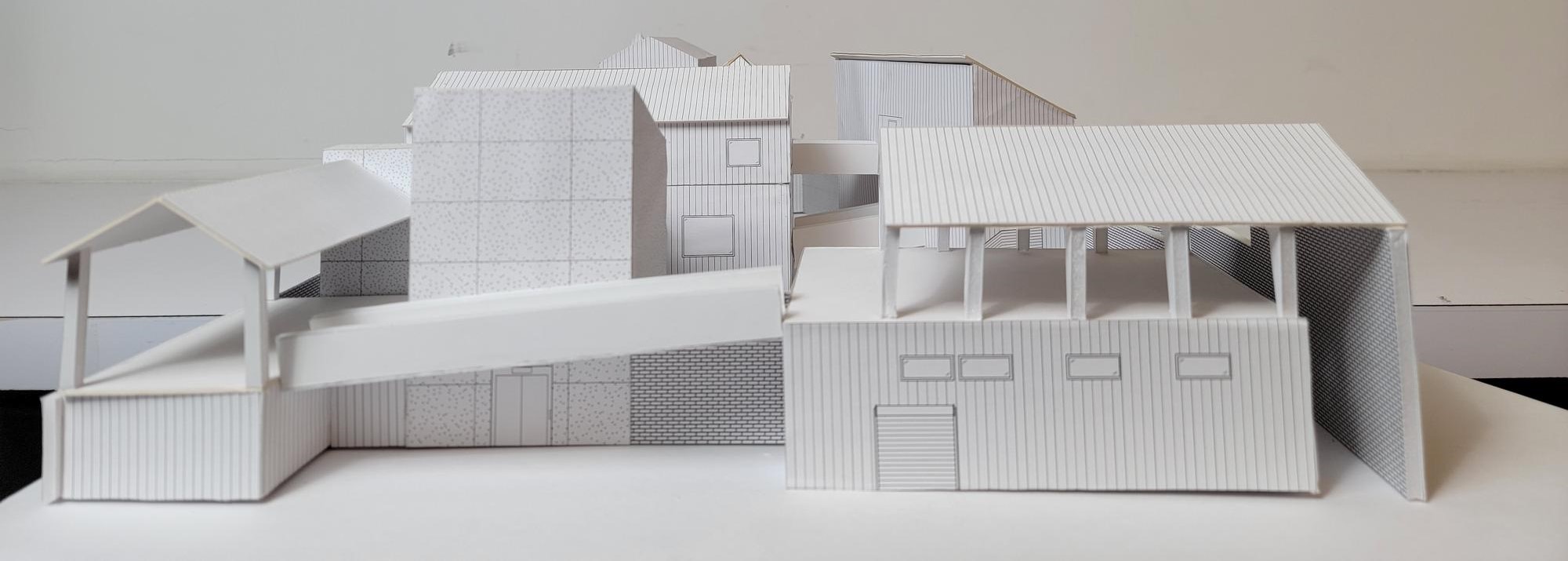

Firstly, prefabricated metal building systems were used for the design of the small campus of buildings. Butler Metal Buildings and their specifications were used as the basis for much of the building design. This is also why the project ended up as a campus of buildings, as prefab metal buildings become very inefficient after a certain size and the program becomes difficult to organize in such a large open space, so several smaller sized prefab buildings were used instead. The dimensions and details of the buildings were based directly off of Butler’s specifications. This strategy accomplished a few things. Firstly, it made the complex program much more easy to organize and divide up. It also honors the philosophy and art of Donald Judd, as his art and his philosophy was largely based off of using what is already available, machining and producing sculptures/building components as opposed to painstakingly making everything custom, non-reproducible, and bespoke. The strategy is not unlike Judd’s concrete panel buildings at the Chinati Foundation, though they were never finished. Additionally, this strategy also honors the surrounding industrial vernacular of the neighborhood, in which most of the other buildings are also prefab metal buildings. It seemed inappropriate to create a shiny new, bespoke building in the middle of an industrial district surrounded by highways and train-yard, and so a prefab system seemed optimal in both taste and expense.

Secondly, as the project is made up of several small buildings, some of which serving as archives for priceless artworks, it seemed necessary to design some sort of security measure that could protect the whole building. While it would be in exceedingly poor taste to build a community center that is built up like a fort, it would be equally dumb (in my mind) to leave the campus wide-open for any random vagrants or hooligans to walk in and cause trouble for the users. Thus, a thin, tall brick wall was built around the perimeter of the site, enclosing the small campus of buildings. The way the wall was laid out, although simple, was very thought out before it made it into the design. In order to make the wall something that adds to the project rather that detract, it was designed to serve as a sort of makeshift facade for the campus, meant to be left bare and austere. With a corridor built into the wall, people are invited inside to explore the campus of buildings that lay obscured by the tall brick wall. Additionally, as the community center is meant to be a place for art in a “rough neighborhood”, the large blank wall acts as a perfect canvas for vandalism and graffiti, which is encouraged by the design. By giving some space back for the community to use however they want (even just through the form of wall-space), the campus of buildings themselves become less of a target for people to impose themselves on. It is not important for every building in the campus to remained untouched, per se, but an archive expects a much different level of treatment than a lobby or cafe, and thus needs some insurance against the routine troubles that come with undeserved neighborhoods.

Lastly, most of the buildings of the campus were designed to be unconditioned by HVAC. This may seem like an absurd decision for a building in Dallas, but it was made very intentionally. With so many separate buildings on the same project, it would be a nightmare to condition them all when, in reality, it would not be so difficult to keep them cool with insulation and cross ventilation. This decision was made, incidentally, after our studio visit to the Donald Judd Foundation, in which we toured many buildings that had no cooling whatsoever. I would have thought that the unconditioned buildings would be miserably uncomfortable in the Texas sun in the middle of the day, but I was surprised to find that they were actually quite nice. Despite having no natural ventilation or efficient insulation, much of the old buildings that make up Donald Judd Foundation are comfortable to inhabit. So, rather than put a dozen HVAC systems in the project, I opted for most of the buildings to just have good insulation and straight paths for air to move through. This happened to cause an issue resolving life-safety codes for the project. Being a big critic of fire-safety codes in America, rather than design something intelligent or efficient to resolve these codes, I instead made ridiculously oversized and blunt fire-stair towers that tower over the entirety of the campus.